Genetic & Morphology Analysis of Nacional Cacao in Piedra de Plata

, by Jerry Toth , 28 min reading time

, by Jerry Toth , 28 min reading time

In 2015 we analyzed the DNA of 47 cacao trees in Piedra de Plata, Ecuador,, in partnership with the Heirloom Cacao Preservation Fund (HCP). We collected the leaf samples under the direction of Freddy Amores, the director of cacao research at Ecuador’s leading agricultural institute (INIAP). The genetic analysis was performed by Dr. Lyndel Meinhardt and Dr. Dapeng Zhang at the USDA-ARS genetic lab in Maryland. Photos of the cacao pods from the sample trees were taken by Carl Schweizer.

In 2015 we analyzed the DNA of 47 cacao trees in Piedra de Plata, Ecuador, in partnership with the Heirloom Cacao Preservation Fund (HCP). We collected the leaf samples under the direction of Freddy Amores, the director of cacao research at Ecuador’s leading agricultural institute (INIAP). The genetic analysis was performed by Dr. Lyndel Meinhardt and Dr. Dapeng Zhang at the USDA-ARS genetic lab in Maryland. Photos of the cacao pods from the sample trees were taken by Carl Schweizer. Of particular importance to us in this study was the genetic footprint of one cacao variety in particular: Nacional. Native to Ecuador, Nacional is the oldest and rarest cacao variety in the world and has long been revered by chocolate makers for its desirable aroma and flavor characteristics. As of 2009, pure Nacional cacao was believed to be extinct. Nacional hybrids are also under threat of disappearing in the face of rapid expansion by the high-yield cacao cultivar known as CCN-51.

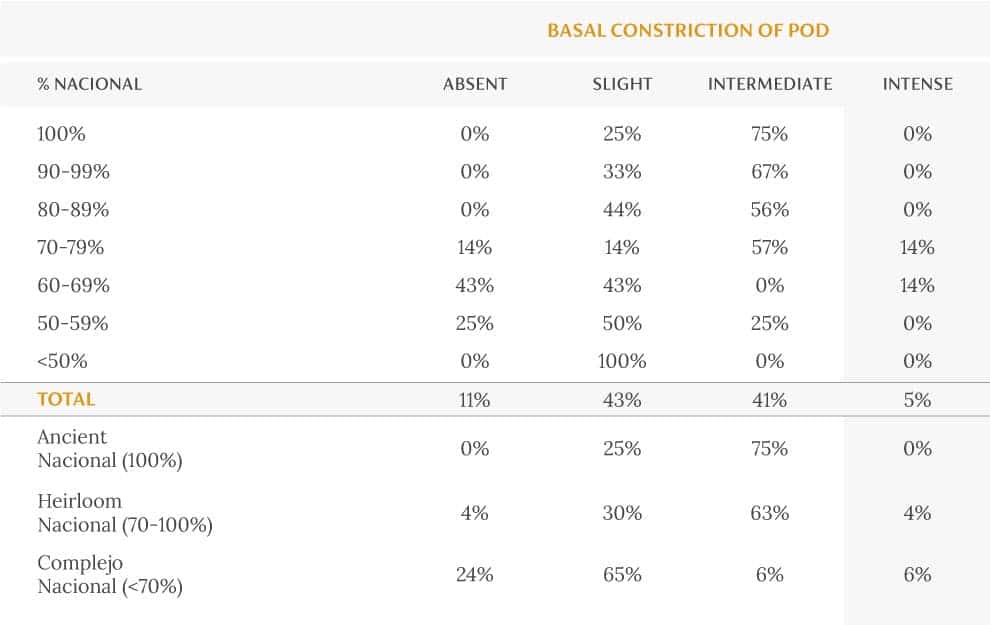

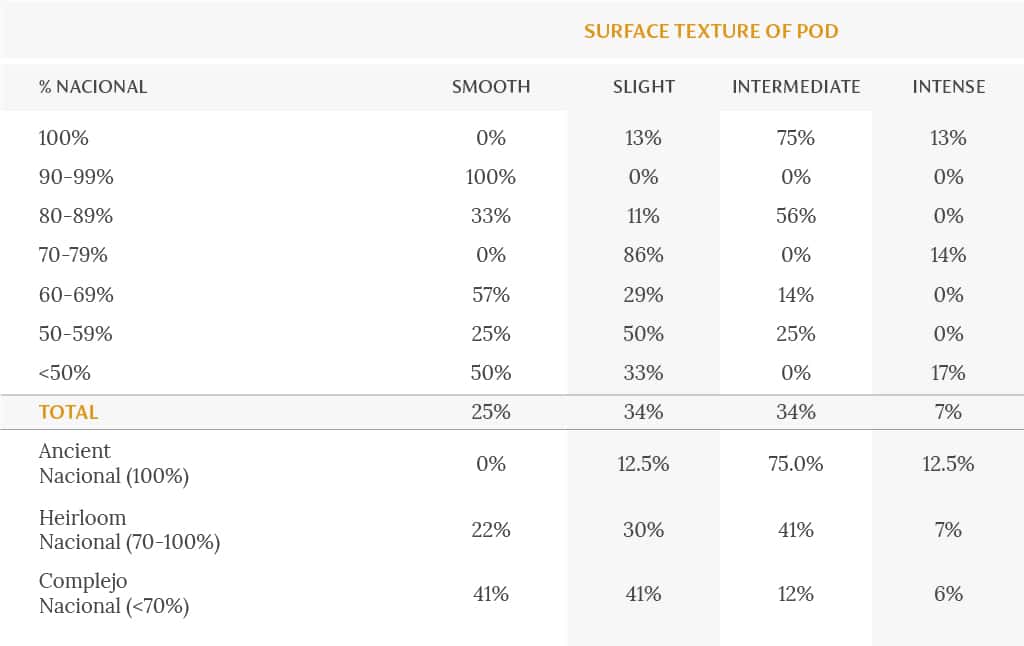

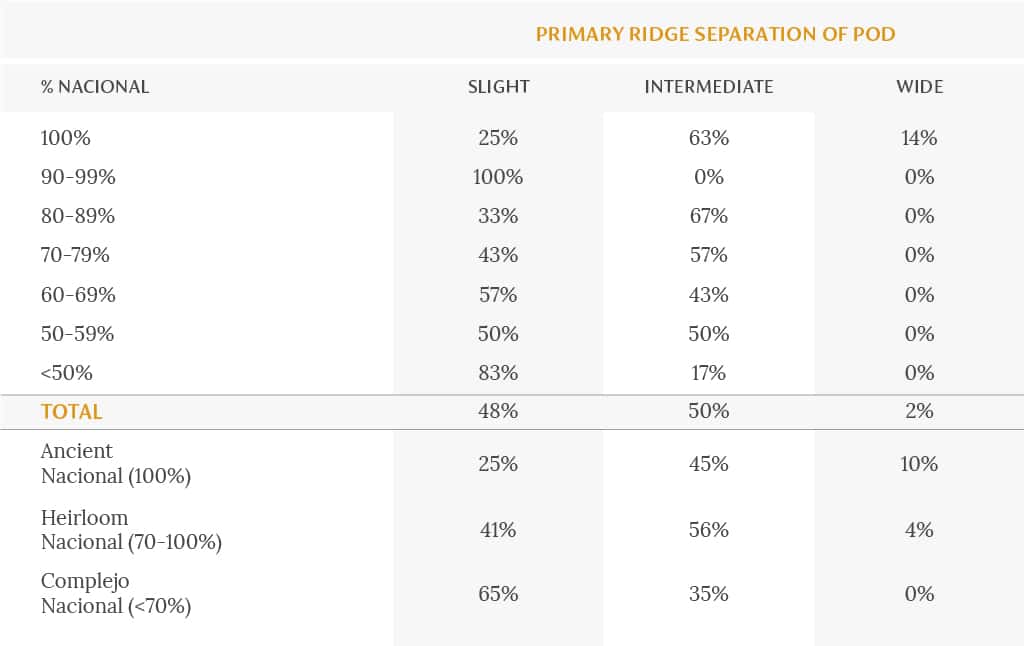

Out of a broad sampling of 47 cacao trees in Piedra de Plata, in which trees of all ages and characteristics were analyzed, nine trees proved to be 100% pure Nacional. In total, 31 of the 47 trees were at least 70% Nacional, and only five of the 47 were less than 50% Nacional. We then used these findings to develop a field guide for the assessment and classification of Nacional cacao to guide our harvest activities in Piedra de Plata when sourcing cacao for To’ak Chocolate. Namely, we wanted to be able to differentiate between Ancient Nacional cacao trees (i.e., trees with a genetic composition of 100% Nacional), Heirloom Nacional cacao trees (70-100% Nacional genetics), and Complejo Nacional (35-69% Nacional genetics) based on physical characteristics of the fruit pods harvested from those trees—specifically color and morphology indicators. We cross-referenced the genetic composition data of the trees with six physical traits of the fruit pods collected from those same trees that were genetically analyzed. These six physical traits include: color, shape, apex form, basal constriction, surface texture, and distance between primary ridges.

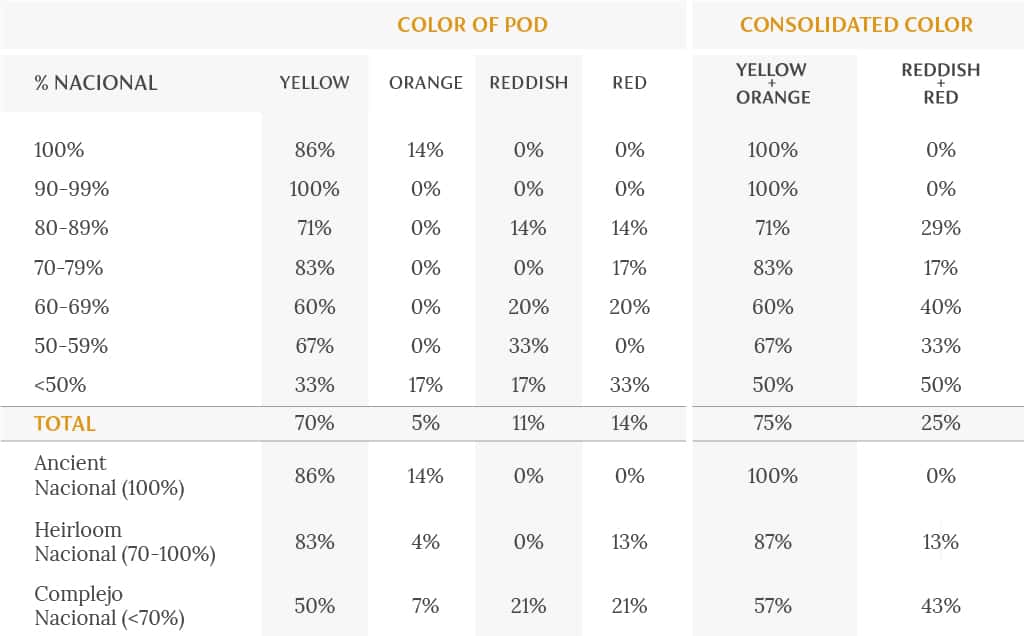

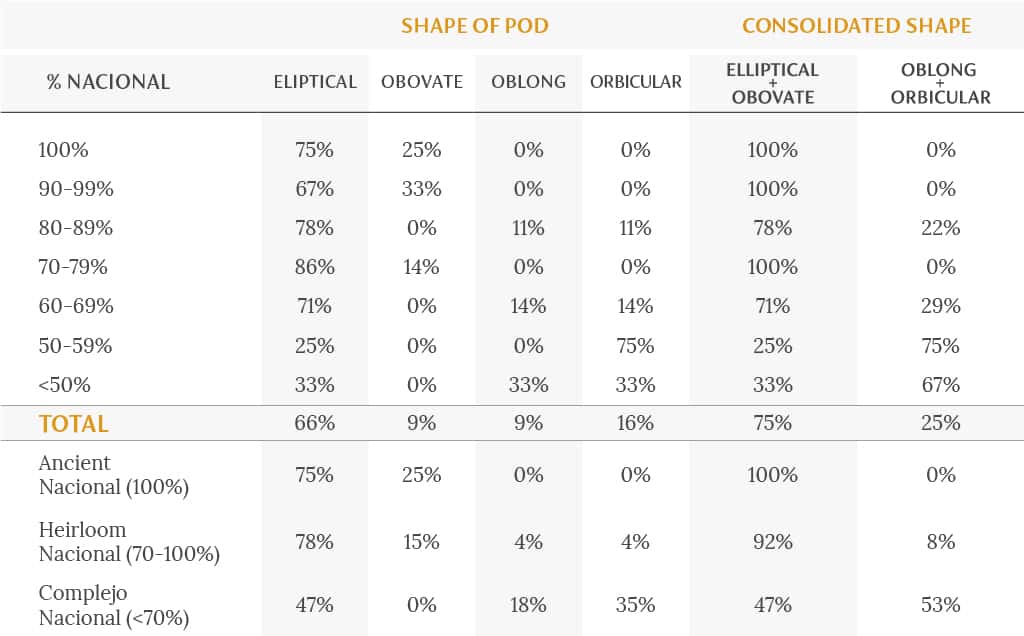

The strongest correlation was found between color and pod shape, with a moderate correlation found with basal constriction. In terms of color, 100% of Ancient Nacional fruit pods were yellow or orange, which drops to 87% for Heirloom Nacional and 57% for Complejo Nacional. Accordingly, the percentage of red or reddish cacao pods rises from 0% for Ancient Nacional to 13% for Heirloom Nacional and 43% for Complejo Nacional. In terms of fruit shape, 100% of Ancient Nacional cacao pods were obovate or elliptical, and 0% were oblong or orbicular. For Heirloom Nacional, the breakdown between obovate/elliptical and oblong/orbicular was 92% and 8%, respectively, and for Complejo Nacional it was 47% and 53%. These findings suggest that, for our purposes in Piedra de Plata, selecting for yellow or orange pods with obovate or elliptical shape, and excluding reddish or red pods with oblong or orbicular shape, is a useful method for distinguishing Heirloom Nacional from Complejo Nacional at the point of harvest.

We acknowledge that a larger sample size would help solidify these results. Currently we are reproducing the nine pure Nacional trees from Piedra de Plata in a protected plot in the Jama-Coaque Reserve, with the aim of conserving this ancient variety and expanding research. To learn more about our conservation efforts, you can read “Conservation: The Noah’s Ark of Ancient Nacional Cacao.”

In 2015 we analyzed the DNA of 47 cacao trees in Piedra de Plata, Ecuador, in partnership with the Heirloom Cacao Preservation Fund (HCP). We collected the leaf samples under the direction of Freddy Amores, the director of cacao research at Ecuador’s leading agricultural institute (INIAP). The genetic analysis was performed by Dr. Lyndel Meinhardt and Dr. Dapeng Zhang at the USDA-ARS genetic lab in Maryland. Photos of the cacao pods from the sample trees were taken by Carl Schweizer.

The genetic composition of each tree was categorized according to eleven “genetic clusters” of cacao, which are considered the primary varieties of cacao in the world today.

The eleven “genetic clusters” (i.e., primary varieties) of cacao:

• Nacional

• Amelonado

• Boliviano

• Contamana aka Ucayali/Scavina

• Criollo

• Curaray

• Guiana

• Iquitos aka Iquitos Mixed Calabacillo (IMC)

• Marañon aka Parinari

• Nanay

• Purús

A few additional notes about terminology and classification should be mentioned here:

• Ucayali/Scavina, Curaray, IMC, Parinari, Nanay, and Purús are often collectively referred to as “Upper Amazon Forastero.”

• Trinitario, a term commonly used to describe cacao varieties, is a complex hybrid of Amelonado, Upper Amazon Forastero, and Criollo.

• The genetic composition of CCN-51, which is fast becoming the dominant cacao cultivar in spite of its poor flavor reputation, is 45.4% IMC, 22.2% Criollo, 21.5% Amelonado, 3.9% Contamana, 2.5% Purús, 2.1% Marañon, and 1.1% Nacional.

Of particular importance to us in this study was the genetic footprint of Nacional cacao, which is native to Ecuador. From what we know from archeological evidence, the earliest evidence of cacao can be traced back to Ecuador over 5,300 years ago, and Nacional cacao is the direct genetic descendent of those original trees. It is the oldest and rarest cacao variety in the world.

By the time Europe acquired a taste for chocolate, in the 18th and 19th centuries, Nacional was the most coveted cacao in the global market, on account of its floral aroma and flavor complexity. According to historical reports, as of 1890, Nacional was still the only cacao variety planted in coastal Ecuador. The landscape began to change in the beginning of the twentieth century with the back-to-back arrival of frosty pod disease (Moniliophthora roreri) in 1917 followed by Witches’ Broom disease (Moniliophthora perniciosa) in 1921.

The arrival of these two fungal diseases marked a great disruption in the Nacional family tree. Between 1916 and 1932, Ecuadorian cacao production decreased by 77%. As Nacional cacao suffered widespread casualties during the 1920s, foreign cacao seeds began to make their entrance, and a century of hybridization ensued. The few Nacional cacao trees that survived the 20th century were frequently cut down and replaced by the new high-yield (and low-quality) sub-variety of cacao called CCN-51. Less than a decade into the 21st century, 100% pure Nacional cacao trees were believed to be extinct. Nacional hybrids (cacao trees with a majority of Nacional genetics) were more widespread, but these, too, are rapidly disappearing in the face of CCN-51. For a more detailed history on the genetic evolution of Ecuadorian cacao over the last five millennia and specifically over the course of the last one hundred years, check out “The Near Extinction of Ancient Nacional Cacao.”

Our relationship with Piedra de Plata began in 2013, thanks to Servio Pachard. Piedra de Plata is a valley deep in the hills of the province of Manabí. It was disconnected from the rest of the country by road until the 1990s. What attracted us to Piedra de Plata is the unusually high presence of cacao trees that are over 100 years old, meaning that some of these trees were born before the arrival of Witches’ Broom and Frosty Pod disease in the early 1900s. It also means that these same trees somehow survived the epidemic and have therefore proven resistant, to some extent, to these diseases.

We hypothesized that some of these old-growth cacao trees in Piedra de Plata were 100% pure Nacional. In addition to their old age, many of these same trees also exhibited the primary indicators of pure Nacional—namely, yellow fruit pods (as opposed to red or reddish); elliptical in shape (as opposed to oblong or orbicular); attenuate apex (as opposed to acute or obtuse); moderate basal constriction of the pod (as opposed to no constriction or pronounced constriction); and reddish stamen pedicels of the flowers (as opposed to unpigmented pedicels).

Before the results were compiled, we were politely warned by numerous people within the industry that we would probably not find any pure Nacional cacao trees in Piedra de Plata or anywhere else. To put the rarity of pure Nacional into context, INIAP collected DNA samples from 11,000 cacao trees throughout Ecuador in 2009, and only six of these trees (out of 11,000 samples!) were 100% pure Nacional. That’s a mere 0.05% of the cacao trees that were sampled.

In addition to these six trees in Ecuador (located in two farms, La Gloria and Las Brisas), a third site with pure Nacional was discovered in the Marañon valley in northern Peru, close to the Ecuadorian border. Aside from these three sites, it was commonly believed that pure Nacional no longer existed.

Fortunately for Nacional cacao, the genetic results from Piedra de Plata confirmed our hypothesis. Out of a broad sampling of 47 cacao trees in Piedra de Plata, in which trees of all ages and characteristics were analyzed, nine trees proved to be 100% pure Nacional. In total, 31 of the 47 trees were at least 70% Nacional, and only five of the 47 were less than 50% Nacional. Shortly following the release of these results, the Heirloom Cacao Preservation Fund officially designated Piedra de Plata as an Heirloom cacao appellation.

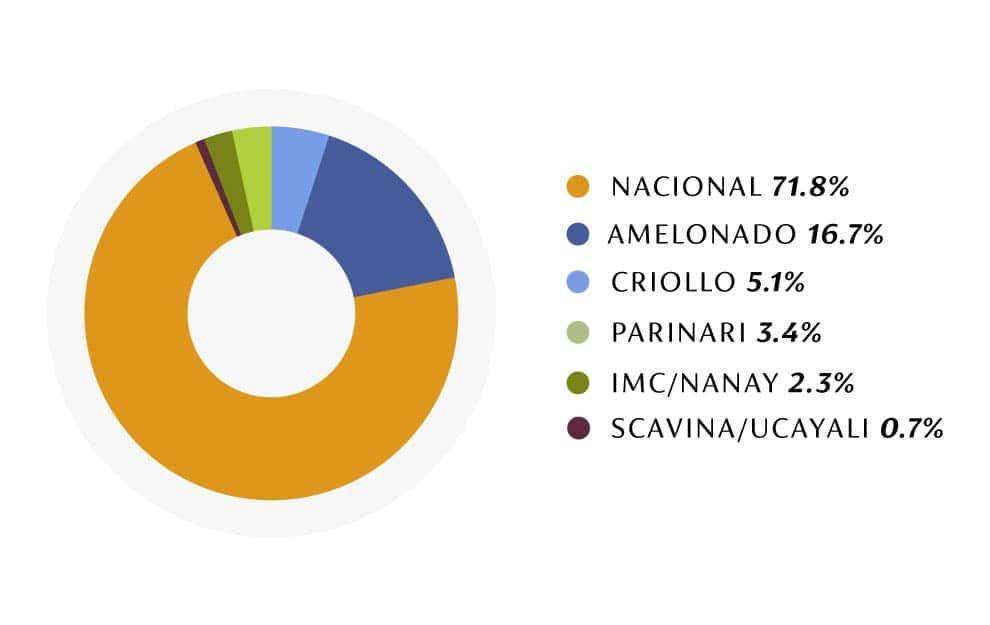

When all 47 samples are looked at collectively, the Nacional genotype represents 71% of the gene pool, which is clearly the dominant genetic cluster. Amelonado, which comes from the lower Amazon basin and is usually distinguished by its melon-like orbicular shape (hence the name), comprises 16.7% of the gene pool in this analysis. The next largest minority is Criollo, which is actually the second-most coveted cacao variety in the world, and represents 5.1% of the genetics. Criollo was domesticated in Central America during the ancient Mayan civilization and is also under threat of disappearing; currently it has a few last strongholds in Venezuela and certain parts of Central America. Parinari, IMC/Nanay, and Scavina/Ucayali can all be grouped into the “Upper Amazon Forastero” category, collectively representing 6.4% of the genetics. Upper Amazon Forastero varieties are credited with greater resistance to Frosty Pod and Witches’ Broom disease.

Amelonado, Criollo, and Upper Amazon Forastero are the predominate varieties that hybridized in Trinidad in the early part of the 1900s and later migrated to Ecuador starting in the 1920s and 1930s, following the outbreak of Witches’ Broom and Frosty Pod disease. This explain the presence of these genetic varieties in cacao trees in Piedra de Plata that are less than 100 years old (i.e., born roughly after 1920).

Our next task was to use these findings to develop a field guide for the assessment and classification of Nacional cacao, specifically to guide our harvest activities in Piedra de Plata when sourcing cacao for To’ak Chocolate. For each tree that was genetically analyzed, we recorded the elevation, coordinates, and estimated age of the tree, in addition to the color and morphology data of the fruit pods. Quantity and size of the seeds, husk width, and some organoleptic characteristics were also measured but not for every sample. A few trees that were tested did not have ripe pods when the leaf samples were collected, so we don’t have pod and seed data on those trees. For each tree that did have at least one ripe pod, this pod was photographed and catalogued, which greatly facilitated the analysis that follows.

We started out with a practical question. We wanted to know how this data could be used to guide our cacao selection in Piedra de Plata to make To’ak chocolate. From a production standpoint, we wanted to be able to differentiate between Ancient Nacional cacao trees (i.e., trees with a genetic composition of 100% Nacional), Heirloom Nacional cacao trees (70-100% Nacional genetics), and Complejo Nacional (35-69% Nacional genetics) based on physical characteristics of the fruit pods harvested from those trees—specifically color and morphology indicators.

The decision to classify cacao with over 70% Nacional genetics as “Heirloom” is partially based on the genetic mapping documentation we received from the USDA, partially based on other Heirloom-designated genetic compositions recognized by HCP, and partially based on organoleptic patterns we’ve observed from various different experimental batches of chocolate we’ve produced from cacao in Piedra de Plata. It should be noted that Heirloom Nacional cacao includes Ancient Nacional.

“Complejo Nacional” is a term coined by INIAP to describe hybrids of Nacional with other varieties, namely Criollo, Amelonado, and Upper Amazon Forastero varieties. Although “Complejo Nacional” is still rightfully considered a “fine aroma” cacao, on par with any other variety in the world, Heirloom Nacional is still superior. In our opinion, Heirloom Nacional is more aromatic, more floral, has more depth, and also exhibits a wider range of the flavor spectrum. Heirloom Nacional is the cacao we harvest for To’ak, with some editions further limited only to Ancient Nacional.

Thus the question became: how do we differentiate between Ancient Nacional, Heirloom Nacional, and Complejo Nacional at the point of harvest? Without the ability to genetically test every single tree in Piedra de Plata, we knew we would need to rely on other indicators—preferably pod color and morphology.

Some morphology descriptions were recorded during the DNA sample collection process and later entered into an excel spreadsheet, which served as a starting point for our in-house analysis. Equally important were the photos of the pods from the trees that were analyzed. I went through every single photo and categorized color and morphology characteristics using the protocol from the “Catálogo de Cultivares de Cacao” published by the Peruvian Ministry of Agriculture in 2009 and the “Morphological Characterisation” guide from the Cocoa Research Center at the University of the West Indies. Specifically, I assessed the following characteristics:

Pod Color

• Yellow

• Orange

• Reddish

• Red

Pod Shade

• Oblong: The length is greater than 2x the width

• Orbicular: The length ranges from 1 to 1.5 x the width

• Obovate: Elliptical with the majority of mass skewed to the bottom half of the pod (i.e., pear-shaped)

• Elliptical: The length is 1.5-2x the width, relatively evenly distributed

Apex Form

• Acute

• Attenuate

• Obtuse

Basal Constriction

• Absent

• Slight

• Intermediate

• Intense

Surface texture

• Smooth

• Slight

• Intermediate

• Intense

Primary ridge separation

• Slight

• Intermediate

• Wide

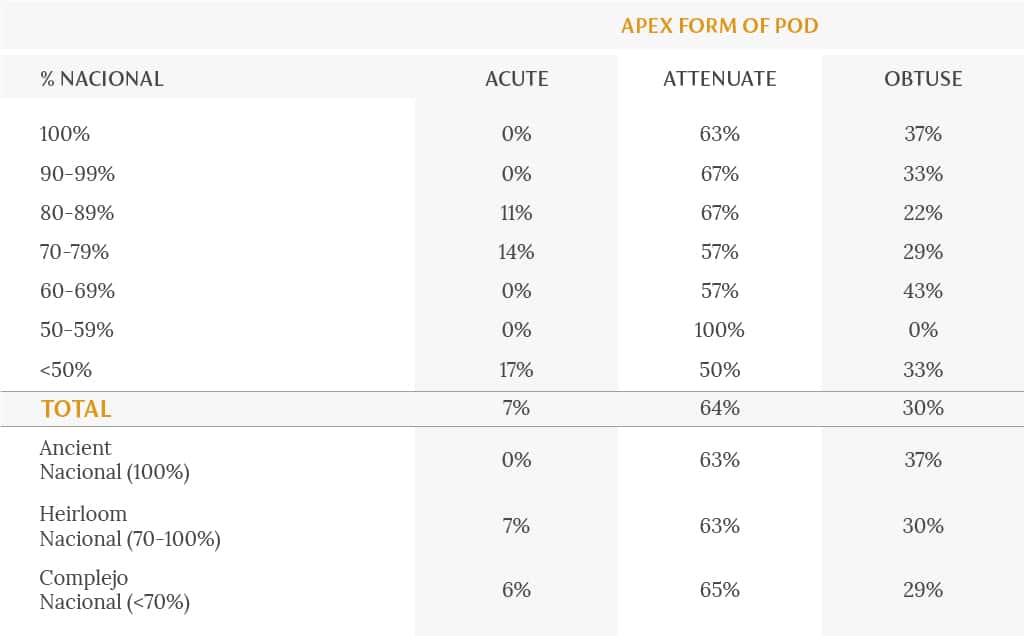

I cross-referenced the color and morphology characteristics with the genetic composition of each sample and organized the results according to tiers of Nacional cacao percentage. The results are below:

The physical characteristics that are most strongly correlated with the Nacional genotype are the color of the pod, the shape of the pod, and basal constriction. Although apex form, surface texture, and distance between primary ridges do not show a meaningful correlation, it should be noted that these characteristics are more difficult to measure objectively. A larger sample size, with more objective scrutiny of each characteristic, may demonstrate a correlation that I was not able to find in this analysis.

The clearest genetic correlation was with pod color. Among trees that were 90-100% Nacional, 100% of the pods sampled from these trees were either yellow or orange. In fact, every pod was yellow except for a single pod from Sample #17, which was orange. It is important to point out that the DNA analysis was taken by leaf sample from the tree itself, whereas the fruit produced by each tree may have been pollinated by another tree. In the case of sample #17, we know that the genetic composition of the mother tree is 100% Nacional, but we don’t know the genetic composition of the father tree. Given the physical characteristics of the pod (which deviate from prototypical Nacional characteristics), it’s reasonable to assume that the father tree has at least a minority of Upper Amazon Forastero, Criollo, and/or Amelonado genetics in its bloodline.

Among trees that are over 70% Nacional, 87% of the pods sampled were yellow or orange, and only 13% were reddish or red. One anomaly in this category was Sample #43, which is 80% Nacional and yet fully red in color. Again, it is likely that the father of this pod has some genetic influence from other cacao varieties. Another anomaly was Sample #26, which is perfectly yellow, elliptical, intermediate basal constriction, attenuated apex, and yet it’s only 58% Nacional. In this case, one is left to wonder if the father tree is in the Heirloom Nacional range, whereas the mother tree falls into the Complejo Nacional range—a bi-category marriage, so to speak. An even more intriguing question, which is beyond the scope of this particular article, is whether the organoleptic properties of the seeds take after the mother or the father.

Aside from these anomalies, for the most part trees with a high percentage of Nacional produced yellow or orange pods. There were zero pods from Ancient Nacional trees that were red or reddish, and only 13% of pods from Heirloom Nacional trees were red or reddish.

As Nacional percentage drops, the incidence of red and reddish pods increases. Among pods produced by Complejo Nacional trees (i.e., trees with less than 70% Nacional), 43% were red and reddish. Among pods produced by trees with less than 50% Nacional genetics, fully 50% of the pods were red or reddish. The data also suggests a correlation between Nacional percentage and pod shape. Among trees that are at least 90% Nacional, 100% of the pods were either obovate or elliptical in shape. With trees that are at least 70% Nacional, the percentage of pods that are obovate or elliptical is still very high—92%. As Nacional percentage drops, the incidence of oblong and orbicular pods increases. Among trees with less than 70% Nacional genetics, only 47% of pods were obovate or elliptical, whereas 53% were oblong or orbicular.

Oblong pods are associated with Upper Amazon Forastero, Criollo, and Trinitario cacao (the latter being a admixture of the first two). Orbicular pods are associated with Amelonado cacao, which originated from the lower Amazon. Not surprisingly, the pods that demonstrate these traits were pulled from trees that registered high percentages of those foreign varieties in their genetic composition.

The last indicator of interest is basal constriction, with 75% of pods from Ancient Nacional trees registering “Intermediate” basal constriction compared with 67% from Heirloom Nacional trees and 56% from Complejo Nacional trees. From a practical standpoint, basal constriction characteristics are less appealing as a field indicator, because the distinctions are often subtle. Basal constriction, along with the rest of the morphological categories, would also benefit from a larger sample size before specific conclusions can be drawn. The general conclusion is that Ancient and Heirloom Nacional pods tend to have sight or intermediate basal constriction and attenuated apex.

After several years of field work, two genetic studies, and a lot of time sitting in front of a computer looking at the results, the conclusions can ultimately be boiled down to these simple principles of cacao selection, which we use to guide our harvests in Piedra de Plata.

1. Just because a pod is yellow or orange, that doesn’t automatically mean it’s pure Nacional or even Heirloom Nacional. But if it is yellow or orange, it has a much higher likelihood of being Heirloom, regardless of shape. And if a pod is yellow or orange and the shape is obovate or elliptical, with intermediate basal constriction, then it has a very high likelihood of coming from an Heirloom Nacional tree. And if, on top of everything, this tree is over 100 years old, there is a chance that it’s 100% pure Nacional—aka Ancient Nacional.

2. Just because a pod is red or reddish, that doesn’t automatically mean that it’s not Heirloom Nacional, although it probably does rule out being Ancient Nacional. If the pod is red or reddish, but the shape is obovate or elliptical and the basal constriction is intermediate, it still may be Heirloom Nacional. But if the pod is red or reddish and the shape is oblong or orbicular, it is most likely not Heirloom Nacional—although it still may be Complejo Nacional.

To play it safe, based on these findings we make a conscious effort to exclusively harvest yellow and orange pods in Piedra de Plata that are elliptical or obovate. This is what we use to make To’ak Chocolate. Although, in the Jama-Coaque Reserve, when I make chocolate for my own personal consumption, I gladly harvest cacao of all shapes and colors. Whether it’s Ancient, Heirloom, or Complejo Nacional, it’s still 100% Ecuadorian dark chocolate.

DNA analysis aside, there are two additional points that also need to be clearly stated. The first point is that genetics alone do not determine the quality of cacao beans. Terroir and cultivation practices also play an important role in shaping the organoleptic properties of cacao beans. Thus we can speak of cacao quality according to the following formula: flavor & aroma characteristics = genetics + terroir + cultivation practices. Heirloom Nacional cacao from Piedra de Plata is special not only because of its unusually high percentage of the Nacional genotype, but also because of the unique soil and climate conditions of Piedra de Plata and the way these trees are managed, from flower to harvest.

The second point is that genetic conservation and genetic diversity are both important. Currently we are reproducing the nine pure Nacional trees from Piedra de Plata in a protected plot in the Jama-Coaque Reserve, with the aim of conserving this ancient variety and expanding research. But this doesn’t mean that we disregard the value of foreign cacao varieties in the Ecuadorian gene pool. In a biological sense, the intermingling of genotypes is a good thing. It promotes adaptation to evolving ecological pressures, such as disease and climate change. After all, genetic diversity is the hallmark of evolution, without which none of this would exist.

Even if it was possible to go back to a situation in which all cacao in Ecuador was 100% Nacional, it would certainly not be preferable to do so. Genetic homogeneity is the reason why Ecuadorian cacao was especially vulnerable to disease in the 1920s. That said, the extinction of Ancient Nacional cacao would be a great loss for Ecuador and also for the world of chocolate at large, both present and future. I think a fair goal is to preserve Ancient Nacional before it disappears, while also continuing to explore the evolution of Nacional hybrids. Ecuador’s reputation as the world’s preeminent cacao origin depends on both of these two approaches.

Additional Reading

References

[1] Motamayor J.C., Lachenaud P., Da Silva e Mota J.W., Loor Solórzano R.G, Kuhn D.N., et al. (2008) Geographic and genetic population differentiation of the Amazonian chocolate tree (Theobroma cacao L.) PLoS One, 3 (10): e3311 (8p.).

[2] Bekele, Frances & Butler, David & Bidaisee, Gillian. (2008). Upper Amazon Forastero cacao (Theobroma cacaoL.) 1: An assessment of phenotypic relationships in the International Cocoa Genebank, Trinidad. Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad). 85.

[3] Zhang D. & Motilal L. (2016) Origin, Dispersal, and Current Global Distribution of Cacao Genetic Diversity. Cacao Diseases: A History of Old Enemies and New Encounters. Eds. Bailey, B.A.; Meinhardt, L.W. Springer, 2016.

[4] Boza E., Motomayor J.C., Amores F., Cedeño-Amador, Tondo C., et al. (2014) Genetic Characterization of the Cacao Cultivar CCN 51: Its Impact and Significance on Global Cacao Improvement and Production. JASHS 139: 2219-229.

[5] Gast_on Rey, Philippe Lachenaud, Olivier Fouet, Xavier Argout, Geover Pe~na, et al.. Rescue of Cacao Genetic Resources Related to the Nacional Variety: Surveys in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Espamciencia, 2015, 6 (E), pp.7-15.

[6] Loor Solórzano R.G., Fouet O., Lemainque A., Pavek S., Boccara M., et al. (2012) Insight into the Wild Origin, Migration and Domestication History of the Fine Flavour Nacional Theobroma cacao L. Variety from Ecuador. PLoS ONE 7(11): e48438. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048438.

[7] Preuss P. (1901) Expedition nach Central- und Sudamerika 1899/1900. Kolonial-Wirtschaftlichen Komitees, Berlin.

[8] Loor Solórzano R.G., Risterucci A.M., Courtois B., Fouet O., Jeanneau M., et al. (2009) Tracing the native ancestors of modern Theobroma cacao L. population in Ecuador. Tree genetics and genomes, 5 (3): 421–433. [20100330]. doi:10.1007/ s11295-008-0196-3.

[9] Benites Vinueza L. (1950) Ecuador: drama y paradoja. [1. ed.] México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

[10] Loor Solórzano, R.G. (2002) Caracterización morfológica y molecular de 37 clones de cacao (Theobroma cacao L) Nacional de Ecuador. Tesis de Maestro en Ciencias. Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, texcoco, Edo de México: 96.

[11] Quiroz Vera, JG (2002) Caracterización molecular y morfólogica de genotipos superiores con características de cacao nacional (Theobroma cacao I.) de Ecuador. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza.

[12] Christian, M. (2012, December) The Mother ‘F’ Tree. C-Spot: Online

[13] Amores, F. (2002) Ecuador: Pasado, Presente y Futuro de la Investigación en Cacao. Estación Experimental Tropical Pichilingue, INIAP.

[14] Yang, JY. Scascitelli, M. Motilal, LA. Sveinsson, S. Engels, JMM, Kane, NC et al (2013). Complex origin of Trinitario-type Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae) from Trinidad and Tobago revealed using plastid genomics. Tree genetics & genomes 9 (3), 829-840.

[15] Garcia Carrión, L. (2009, August) Catálogo de Cultivares de Cacao. Ministeria de Agricultura de Perú, Despacho Viceministerial.

[16] Morphological Characterisation. Cocoa Research Center at the University of the West Indies. Online